We’ve recently been working with Ulster University, Smart Video and the Donegall Pass, Sandy Row and Markets neighbourhoods to produce a video, narrated by Donzo, which explores the fascinating history of these inner city communities. We’ll be able to share that with you soon!

As part of the script creation, we researched many of the old buildings and famous people in those areas. One that did not make the final cut of the video, but nevertheless has a fascinating history, was the Belfast Union Workhouse, located off the Donegall Road. So we thought we would share it with you as a taster of what you can expect from the video.

The Belfast Workhouse

Opened in 1841, The Belfast Union Workhouse was built to house 1,000 inmates. Today the site houses Belfast City Hospital. The old Fever Hospital is one of the few remaining original buildings.

While the Belfast of the 1840s might have looked prosperous compared to other Irish cities – William Thackeray described it as ‘hearty, thriving and prosperous, as if it had money in its pocket and roast beef for dinner’ – in fact there was widespread and endemic poverty.

The rapid growth of Belfast’s population in the previous twenty years had led to overcrowding and insanitary conditions. By the middle of the 19th century, Belfast had one of the highest death rates of any town in the United Kingdom – in 1851, infant mortality was so high that the average age at death was 9 years.

The Famine in Belfast

When the potato blight appeared in Ireland in 1845 the workhouse was already established. However, only those in severe distress, often on the point of death, would apply for admission. So although hunger, destitution and disease was widespread, it was initially underused.

But by 1846 Belfast was in the midst of the famine and a recession in the textile industry, and by the end of that year the workhouse was full to overflowing, while the local soup kitchens were feeding 3,000 people a day.

By the spring of 1847 there were 1,500 people in the workhouse and local papers were carrying daily stories of death from starvation and destitution. Tents and sheds had to be added to the workhouse to cope with the overflow.

Belfast not only had to deal with its own population – the authorities also had to cope with a steady flow of people coming in from the surrounding countryside, looking for employment, food or a passage out of Ireland.

In addition, after 1847 Belfast became a dumping ground for Irish paupers expelled from Britain, particularly from Scotland. That’s one of the reasons no-one knows how many died from the famine in Belfast, because overall the city’s population increased over the 1840s.

But what we do know is that nearly 1,500 people died in the workhouse in 1847, where every other year in that decade saw around 200 -300 deaths recorded there.

The Typhus Epidemic of 1847

The overcrowding of the workhouse meant that famine was followed, almost inevitably, by an epidemic of typhus in 1847. By the summer, 70-80 people were reported as dying of typhus in Belfast every week, with many more going unrecorded.

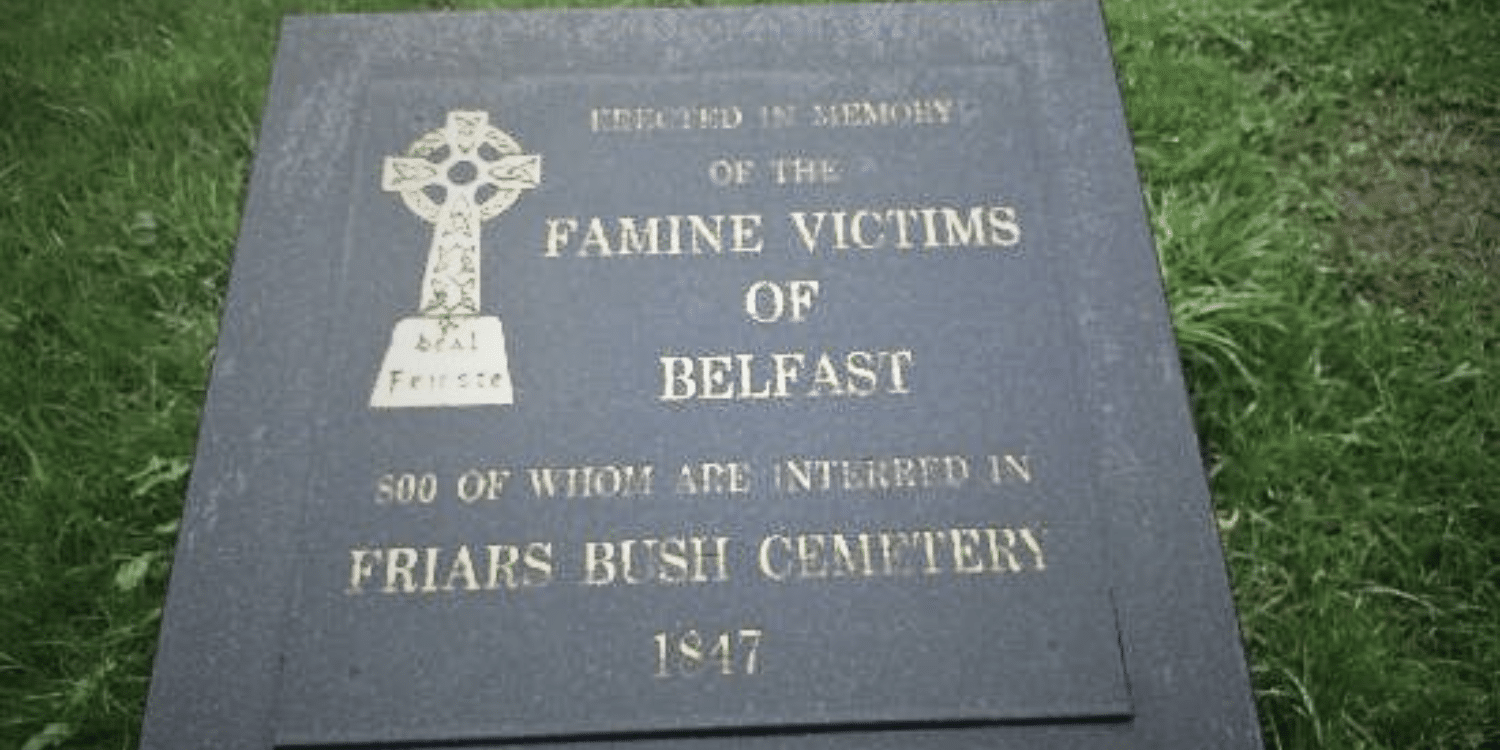

The graveyards were overcrowded, with Friars Bush cemetery described as “so much choked with the dead” that the sextons had to dig square pits that could hold 40 coffins at a time. In Shankill graveyard “coffins were heaped upon coffins until the last one was not more than two inches underground”.

Belfast famine victims memorial at Friar’s Bush cemetery

The Cholera Epidemic of 1849

The typhus epidemic of 1847 was followed swiftly by a cholera epidemic in 1849. The first case was found in the workhouse in January, and from here it spread rapidly across the city.

By the end of year 3,448 people had been treated for cholera and 1,126 had died. Again, poverty and overcrowding as well as contaminated water were important factors in its spread – as a Dr Browne wrote in a letter to the Northern Whig newspaper:

“…let us look at Tea Lane and Sandy Row. In both, cases of cholera have been numerous, and, in many instances fatal: both of these localities are notorious for filth, and its sure accompaniment, disease!”

In the decades after the Famine, Belfast’s rapid rise to prosperity meant that the suffering of the poor in the 1840s was largely forgotten. But it left a lasting legacy, and the fear of the workhouse cast a long shadow over future generations in Belfast.

© Ulster Museum 2008 – Elderly inmates of the Belfast Union workhouse ca. 1905

In fact, the workhouse didn’t close until 1948, when the poor law system was finally swept away and Northern Ireland established a comprehensive welfare state with free health services. It became the Belfast City Hospital and you can still see a few buildings from the old workhouse days on the site.

If you would like to find out more about the social history of Belfast, we’ll be sharing the video when it’s launched, so make sure you sign up for our monthly updates so you don’t miss it. Or book yourself a spot on our Best of Belfast tour, where our team of local guides will introduce you to hidden history, fantastic street art, beautiful architecture and fascinating stories of Belfast’s citizens from the past and present.